Did America become the No 1 golfing country even before a bruising first Ryder Cup loss in 1927?

By the end of the 1920s decade, writes Ross Biddiscombe, when the Ryder Cup would finally become an officially recognised event, there would be certainty about whether Great Britain or America was the home of the best golfers in the world. It had been an intense discussion within the sport for years.

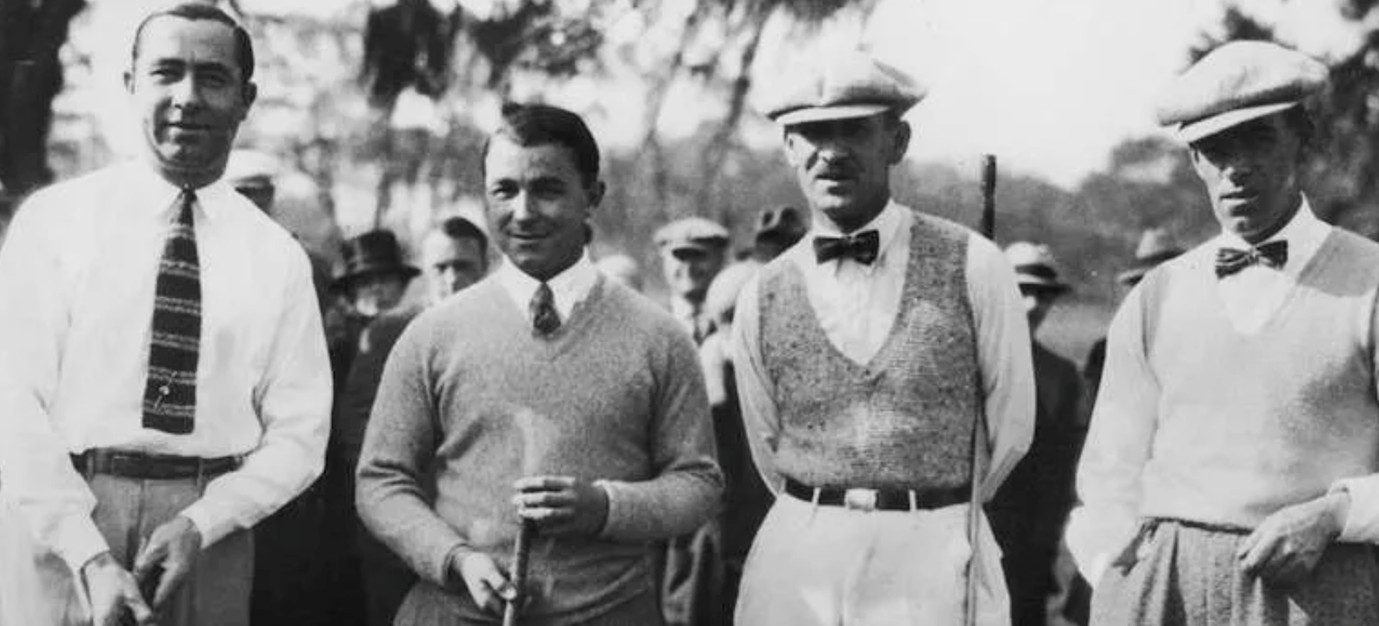

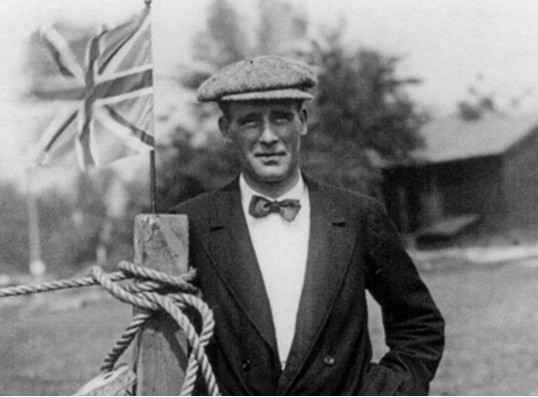

In a book by top British golfer and Open champion George Duncan (pictured above), written in 1920 with the help of the great golf author Bernard Darwin, ‘the American question’ was debated: just how good were the Yanks and who was the biggest threat to the supremacy of British players?

The chapter ‘Present Day Golf’ acknowledged that the sport in the US was “developing at a great rate…and they have a few amateurs quite capable of winning our Amateur Championship”. The writers believed a team match was needed to confirm which was its leading nation.

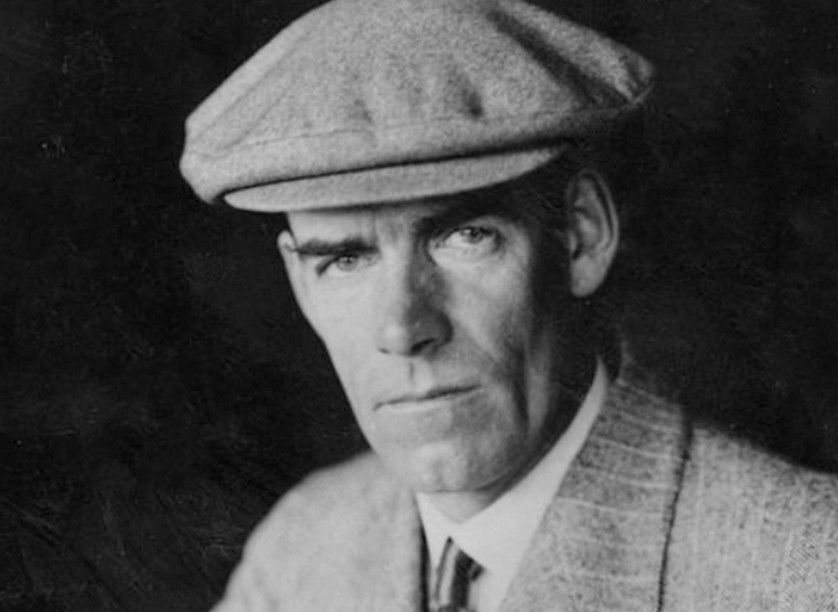

Duncan believed the best golfer in America was not an amateur but a fellow pro, Walter Hagen, who finished only six shots behind the Open champion on his first trip to St Andrews that year. “He has the best methods,” stated the book. “I believe in his square stance and fairly upright swings and his open club-face.”

Duncan admitted that, with more links experience and better coaching, American players like Hagen would win The Open. “The older school of ‘home bred’ American golfers copied the school imported from St Andrews, with a long, flattish swing and a tendency to make all the shots come in from the right. One can get round St Andrews with a bit of hook, and equally well without it. But it is a good thing to err on the left-hand side there.

“In the last few years, America has imported half a dozen first-class players and, better still, coaches who England could ill afford to lose. Most of them are converts to the new and better methods than those they had originally, and this makes it all the easier for them to impart their knowledge.”

This US-centred vision of golf’s future was not in isolation. A fine English amateur player, Harold Hilton who had himself won the Open as well as both the British and US Amateur titles, said in 1923: “There can be no doubt that the American player of the game has somewhat rudely annexed that presumptive hereditary right of ours…To put the matter in the very plainest language, American players of the present day are better golfers than their British cousins.”

The events of the 1920s would prove these forecasters correct: ex-pat Scot Jock Hutchison (in 1921 and a newly minted American citizen), Hagen (four times), Bobby Jones (twice and then again in 1930); and Jim Barnes (once) were all Open champions during the decade. No British player won the championship from 1920 until Henry Cotton’s victory in 1934.

The trans-Atlantic rivalry was escalating fast and when GB took a 9½-2½ pasting in America at the inaugural Ryder Cup in 1927, it shook the psyche of the British golf community. Many weak excuses – the burden of travel being the most obvious – were provided to explain that the loss was just a temporary fall from grace. But when the Yanks put up a stern fight and eventually lost only 7-5 in 1929 in Moortown, Yorkshire, it underlined that New World golfers now ruled the world, even in defeat.

For the longer, unabridged version of this story, click https://open.substack.com/pub/rossbidd/p/ryder-cup-series-part-3-british-domination?r=2jbyei&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web&showWelcomeOnShare=true

Ross Biddiscombe is the author of Ryder Cup Revealed: Tales of the Unexpected & his regular Ryder Cup posts are also on Substack; click here for the app https://substack.com/app and subscribe for FREE to receive extra Ryder Cup stories and other sporting journalism

Next time: Ryder Cup 2025 Series Part 4 discusses the questions of money including how and why players are paid for playing in golf’s greatest team event,